Mexico’s Rich Theatrical History: A Retrospective

The Ghosts of Theatres Past In Mexico, Missouri

Before the days of commercial radio and long before TV became a staple in every household, live entertainment and movies were the entertainment choices for Mexicoans from the late 1800s through the mid 1900s.

From traveling circuses, chautauqua events, and tent shows like Toby & Suzy and Punch & Judy, Mexico advanced through opera houses to open-air theatres, on to movie theatres and drive-in movie theatres over the years. Today, we take a look back at the history of Mexico theatres of days gone by.

According to early records, the first theater showings began around 1870 in the upper floors of what used to be the Ledger building on the northwest corner of Washington & Monroe. However, things began in earnest when an opera house opened in Mexico and put the town on the kerosene circuit of traveling stock companies.

According to the Historical Dictionary of American Theater, the kerosene circuit was: “low-budget touring companies of no more than eight troupers might be relegated to performing in country towns so small that kerosene lamps were still used for lighting the halls. ‘Playing the kerosene circuit’ meant making the best of a long succession of one-night stands in ill-equipped second-story halls over commercial space in towns of perhaps 300 to 1,000 inhabitants.”

A Tale of Three Opera Houses

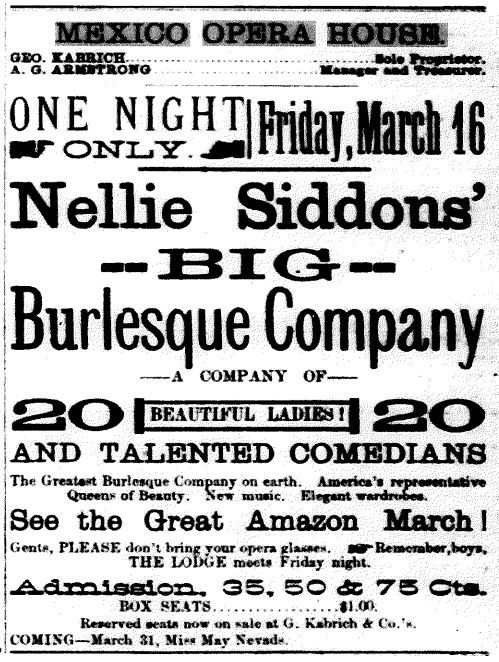

The first of the opera houses to open was owned by George Kabrich and was in the building on the northwest corner of Washington & Jackson. It was on the third story of the building and according to performers, it was the best theatre in outstate Missouri.

Some of those early performers included nationally known comedian Eddie Foy, credited with keeping the crowd calm during the Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago on December 30, 1903… he was able to escape by crawling through a sewer. Sisters Cecil and Edna May Spooner, who went on to Broadway and motion pictures performed in stock companies at the Kabrich, as did Ike Payton. Payton performed with the successful Corse-Payton Stock Company and later owned one of the finest vaudeville theatres in Philadelphia and became a millionaire.

The Kabrich had a 22 by 36 feet stage, seated 800 to 1,000 (depending on the remodeling timeline) and had 2 drop curtains.

In a February 2, 1882 article in The Mexico Ledger, George Kabrich was renovating the opera house from top to bottom, including increasing capacity to 1,000 with 400 gradually raised orchestra chairs, 200 chairs in the parquet area, 150 in the balcony, and another 250 in private boxes encircling the entire building.

Ab Armstrong was one of the last managers of the Kabrich and Frank Hazard, a Spanish-American War veteran and long-time Wabash Railroad employee, was the property boy.

The Kabrich closed in 1893 and it’s stage collapsed around 1916. The Masons used the upper floors as their lodge for a time and during World War II, the flooring of the old opera house was sold to the Audrain County Fair Association.

The third floor of the building was removed in 1971 by Ralph Robinson Construction Company of Kansas City who constructed a new roof on the floor of the old third story.

The Ferris Grand Opera House was built in 1889 by G.D. Ferris at 213 West Monroe. Mexico’s H.D. Hunter was the architect who designed the $16,000 building with construction handled by John Ballew. The walls of the building were 18 inches thick. The house opened with Mikado in August 1889.

The Ferris Grand had a stage 53 by 40 feet with a proscenium opening of 36 feet and seated 1,400. Frank Hazard was the stage manager.

Miss Leslie Ferris was the owner of the building when it was destroyed by fire on January 21, 1913.

The P.M. Morris Opera House was located on the third floor of the old Jefferson Hotel on the northeast corner of Jefferson and Promenade.

The New Grand, built out of the remodeled Smith Brothers Garage on West Monroe where the Ferris Grand had been, opened in 1924 and seated 800.

A fire of unknown origin was discovered at the New Grand at 3:55 Friday morning, April 29, 1927. The fire, described by The Mexico Ledger of the same date, was the most disastrous since the Ringo Hotel fire of April 19, 1918.

A north breeze fanned the flames and ultimately carried sparks and charred tinder “all over south Mexico” and “Hardin Park was well dotted with the black embers” according to The Mexico Ledger, whose office was also damaged during the fire, mainly by water damage.

The New Grand was a total loss, estimated at $90,000, including $12,000 worth of fixtures, stage and motion picture equipment owned by Universal Chain Theatrical Enterprises of New York.

From Vaudeville to Motion Pictures

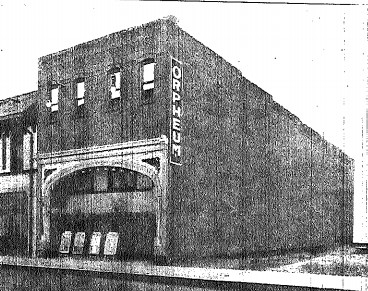

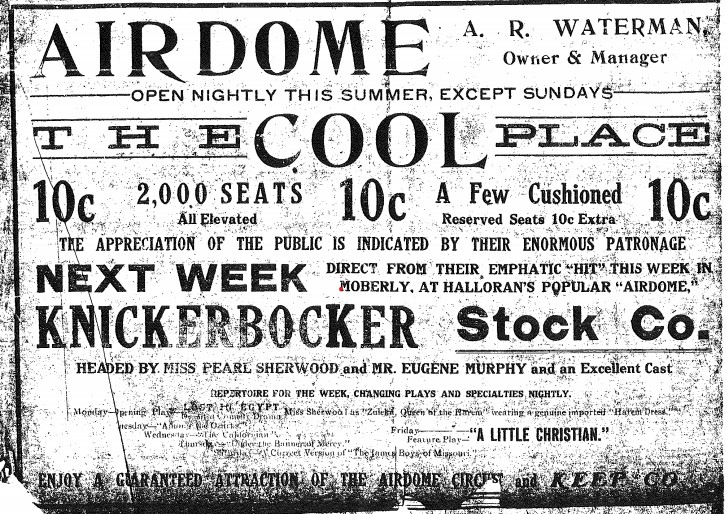

In September, 1910 a businessman from Mason City, Iowa, Sydney C. Thompson announced plans to build a vaudeville theatre. It was to be two stories and built of concrete blocks with the exception of the front which would be of pressed brick. The theatre was to be named The Orpheum and would seat 1,000 and have not only a steam-heating plant, but also a fan arrangement for summer that would change the air continuously “without disturbing anyone.” The cost? $15,000.

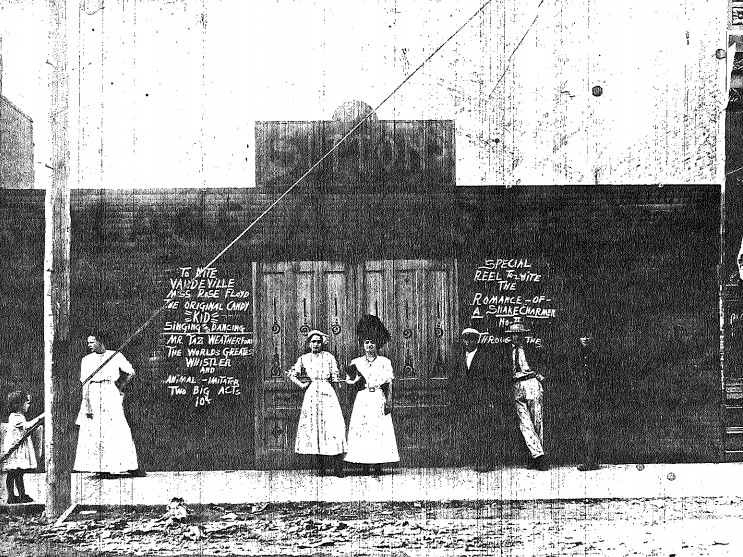

Mr. Thompson also at the time owned the Suttons Palace Air Dome at 220 West Monroe, an open-air theatre for summer amusements from May to September.

A minor fire at the Orpheum in late June of 1912 could have had a much worse outcome had it not been for the clear-thinking of musician Miss Eugenia Crockett. The insulation on an electric wire caught fire in a blinding flash and the entire audience sprang to their feet. Miss Crockett continued to play while cooler heads endeavored to quiet the crowd. The building was nearly fireproof and in the event it had been worse, the crowd would have been able to escape.

In July of 1917, Thompson announced he was leasing the new theatre in the Alamo Hotel at the corner of Liberty and Jefferson from Gallaher and Strief. The 800-seat theatre would host “high-class road shows and moving pictures” and would be called the Rialto with a large electric sign carrying the name on its front.

The Rialto’s stage was slightly larger than the Orpheum’s and the stage curtain was a scene of Columbus’ fleet of voyagers seeking America.

While the Orpheum had a policy of “Always 10 Cents”, the Rialto showed pictures “sold with understanding they be shown at higher prices than 10 cents.”

Tragedy would strike the Orpheum January 3, 1920 when a fire, possibly started by would-be robbers, claimed the life of Sydney Thompson’s father, 51-year old Osman B. Thompson who was living in a 2nd-floor apartment in the building. The building was all but destroyed, but would be rebuilt and expanded.

The new building in the 100 block of West Promenade would seat 1,100 with wider aisles and a pipe organ. As Thompson’s lease on the Rialto was running out in September of 1920, much of that equipment was moved to the new Orpheum.

Mexico’s Crown Jewel

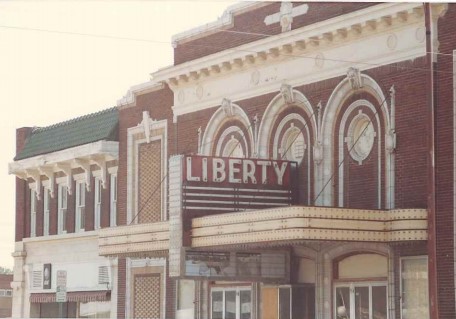

In March of 1920, it was announced that Mexico would be getting a new theatre, called the Liberty. It was to be built “at once” on the corner of South Jefferson and Liberty Streets and would be modern to the last detail according to Cassius M. Clay who was in charge of construction. The 70 feet wide by 105 feet deep building was expected to be completed around June 1st with Film Securities Company building the structure.

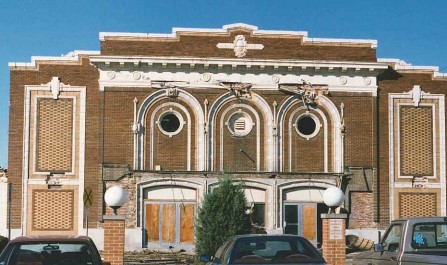

The Liberty opened at 301 South Jefferson with the matinee performance of “Something To Think About” starring Gloria Swanson on Monday, November 1, 1920 and according to a front-page article in the November 4th Mexico Weekly Ledger it “is the finest theatre of its kind in a city the size of Mexico in the world. it cost over $100,000 and is equipped with every modern convenience known to picture theatre architecture and is considered the finest theatre of its kind in the state outside of one theatre in Kansas City.” The Ledger went on to describe the Liberty’s accoutrements:

“The house is perfect in detail. When you enter the handsome marble wainscoted lobby, with a manager’s office at one end and a ladies’ rest room at the other, you are met by a classic scheme of decoration, done in bronze and black and light gray and tan that is most attractive. The foyer of the theatre is equipped with toilets for men and women, and the floor, as that of the lobby, is handsomely tiled.”

“The seats, which accommodate 1500, are leather upholstered and made especially for the Liberty. They are comfortably arranged, giving both the first floor and the balcony a perfect view of the screen. Gold, bronze, and old rose tints are used lavishly in the interior decorative scheme with a ceiling in light gray. The lights are all indirect and give a soft glow which lends a subdued affect that is most attractive. They are placed along the walls in beautiful containers.”

“The screen is a special one, of the newest type and the projection room is wonderful, having two of the latest model Simplex machines and a spot light machine, besides every convenience for the operator.”

“Handsome draperies cover the screen between performances. The $18,000 organ, so arranged that the pictures will perfectly synchronize with its playing is presided over by Chas. Pigg, one of the best pipe organists in the country and whose ability in this field requires no introduction to a Mexico audience. The organ has a complete equipment in every detail.”

“To perfectly appreciate the theatre and its wonderful features one must see it. It is heated and ventilated by the newest ideas along this line and in summer the temperature will be kept down with the aid of ice. Nothing has been overlooked that in any way would tend toward making the public more comfortable. The air is exchanged every minute with the aid of huge electric fans with suitable ducts through which the air can pass from the building at one pint while fresh air enters at another.”

The main entrance to the Liberty was on Jefferson Street with another entrance for black patrons on Liberty Street. Mexico, as was the rest of the U.S. at the time, segregated. Until 1962 when the Liberty was desegregated, black patrons were relegated to the balcony.

The stage of the Liberty was six feet deep to accommodate vaudeville and according to rumor, contained a trap door that lead to the basement under the stage. That has not been substantiated.

A.H. Whitney was the first manager of the Liberty and at the time of its opening, the ticket office was in the center wall of the lobby and the intitiat picture offerings included a news or pictorial reel followed by a two-reel comedy and a feature.

Movies with sound, or “talkies”, came to the Liberty April 24, 1929 beginning with “The Voice of the City”, directed by Willard Mack who had previously appeared “on the legitimate stage” at the Ferris Grand before his directorial days. The sound system was upgraded in August of 1929 to the newest R.C.A. Photophone device with the first film shown using the new technology “The Thunderbolt” starring George Bancroft, Fay Wray, Richard Allen, Tully Marshall, and Eugenie Besserer. The last silent picture at the Liberty was shown on Saturday, August 24, 1929, silencing the $18,000 Robert Morgan Pipe Organ and ending organist Charles Pigg’s entertainment at the theatre.

Captain Pigg was the piano instructor at Missouri Military Academy beginning in 1920 after having served in the U.S. Army during World War I. He served from April 27, 1918 until June 11, 1919, having left from Mexico with a group of 20 other men on April 27th for Camp Funston, part of Fort Riley, Kansas. Pigg was not only a concert pianist and organist, but also a composer. His piano training came from Emil Liebling who himself was trained by Franz Liszt in his native Germany. Pigg also trained under Arnold E. Guerne, director of the Hardin College Conservatory of Music in Mexico.

Always wanting to offer the latest in technology, the Liberty installed new Carrier air conditioning in 1933. Installation started in June and was completed in December and used a turbine compressor driven by a 100 horsepower motor, and a huge fan driven by a 10 horsepower motor to circulate 30,000 cubic feet of air through the auditorium each minute. Had this been used to make ice, it would have produced 52 tons per day, more than the ice plant in Mexico could produce.

Additional sound improvements and redecoration came along in May of 1935 when new acoustic tile were placed on the ceiling to dampen the sound of the loudspeakers. Film sound recording had improved and included higher frequencies, requiring the dampening to improve the listening experience. New spring-bottom seats were installed and a new tile Mastipave floor laid in the Liberty. The existing seats were moved to the Orpheum Theatre in hopes of reopening that hose “provided conditions improve.” A new blue velvet stage curtain and draperies were installed as well.

Friday, February 5, 1937 saw an inauguration in Mexico. No flags were waved or speeches made, but the Liberty unveiled a new $7,000 system improving sound and picture quality. Two new Motiographs, on which the reels are run off, were first used. The same system was at the time used in Radio City, New York and the new sound systemwas used nowhere else in the Midwest outside of the Coliseum in Chicago. The new sound system used a pinpoint of light passing through the “sound track” of the film to a photo-electric cell, converted to electric current and then sent to the amplifying unit. The system was so sensitive that if a wisp of smoke passed through the beam of light, patrons would have heard a sound like a drum beat and if it were interrupted by a toothpick, it would create a sound similar to an explosion.

In October of 1940, Frisina Amusement Company of Springfield, Illinois leased the Liberty as well as the Rex (more on the Rex follows) for a period of 20 years. They committed to a $25,000 improvement plan for the two theatres. The renovations started just before Christmas of that year that included moving the ticket booth from the lobby to the outside and replacing the original glass canopy on the front with an entirely new one. The auditorium was also boxed off from the lobby corridor and doors placed at each aisle.

Third Time’s The Charm?

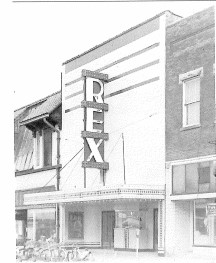

The Orpheum was completely remodeled in 1935 after having been shuttered for five years. The architect for the project was O.W. Stiegemeyer of St. Louis who had designed the Liberty. The entire interior of the theatre was gutted and a “modern flat balcony” was installed as were new chairs and an acoustic ceiling. The entire front of the building was rebuilt as well.

The Orpheum didn’t last long in this incarnation and ultimately re-opened in December 1939 as the Rex with first-run shows Friday and Saturday nights at 7:30 and 9:30. There were initially no matinees and it was closed Sundays through Thursdays. Children’s tickets were ten cents and adults were fifteen cents.

Frisina leased the Rex together with the Liberty in 1940 and after years of disuse, pulled the equipment from the building in 1965 and the City of Mexico had the building at 118 West Promenade condemned in 1966 after it was found to be unsafe and rat infested.

The vacant lot, having been in the estate of Mrs. Gussie Phillip, was given to Audrain Hospital in 1969, thus ending the tale of one of the most disaster-plagued theatres in Mexico.

Sosna Comes To Town

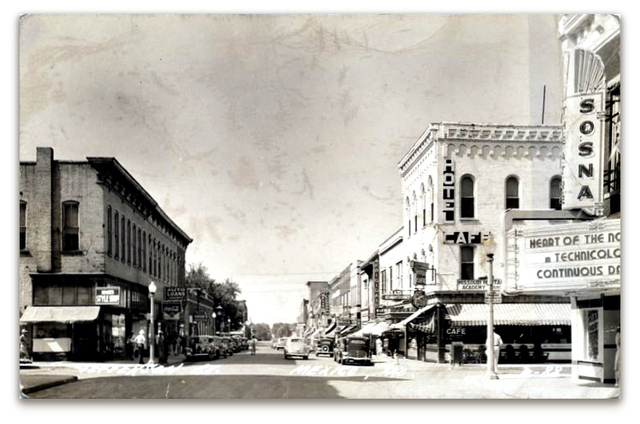

Louis M. Sosna moved to Mexico from Moberly to open his theatre in the former Lane building at the southeast corner of Promenade and Jefferson. The main entrance of four doors faced Jefferson with two side exits onto Promenade. It opened in July of 1940 with the Dick Powell & Ann Sheridan film “Naughty But Nice.”

The interior was described as having turquoise blue velour curtains, thick crestwood carpet and 12-spring leather upholstered seats.

The Sosna brothers began in the theatre business in 1919 in Iowa with Louis owning theatres in Ottumwa, Cedar Rapids and Victor after his service in World War I. Sam Sosna took over the Varsity Theatre in Manhattan, Kansas in 1931. The third brother, S. Zanvil Sosna was a graduate of Washington University in St. Louis and took a financial interest in the Mexico operation. In 1936, Louis opened the Sosna Theatre in Moberly.

The Sosna Theatre in Mexico closed in 1944.

Motoring to the Movies

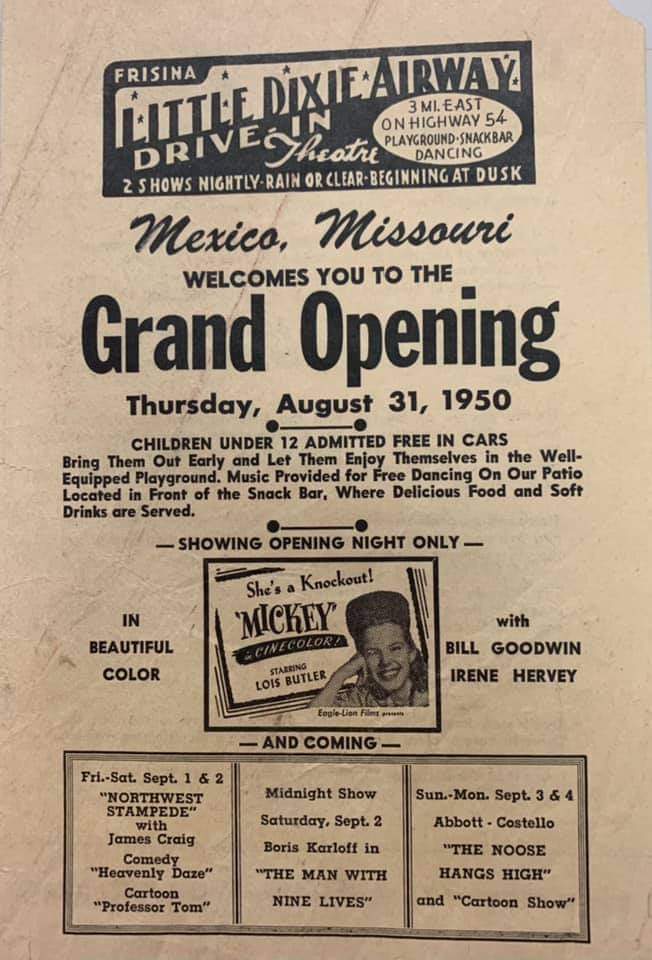

Americans tastes were changing post World War II with the automobile taking full hold. Movies changed along with that and the drive-in theater was born. Mexico was no different. The Frisina Amusement Company purchased 15 acres east of Mexico from John and Ray Hagan and on August 31, 1950 the Little Dixie Airway Drive-In opened for business.

It was owned and operated by Frisina Mexico Theatres Limited and could accommodate 500 cars. The first film shown on the 52 by 42 feet screen was “Micky” starring Lois Butler. The Little Dixie Airway Drive-In closed for the season in the fall of 1982 and wouldn’t reopen.

The Ones That Never Were

There were plans for two other theatres (at least) in Mexico that never materialized, or at least not that researchers have found.

The first was another outdoor theatre like the Sutton Airdome and was to be built on West Promenade, roughly across from the Orpheum according to an April 18, 1921 story in The Mexico Ledger. It was to be built by the Liberty Theatre Company and plans had been finalized with construction to start May 1st and be finished by the end of May. It was to have held 1,000 people and would have operated until cool weather.

The other theatre, also to have been erected and operated by the Liberty Theatre Company was the Rivoli. It was to seat 600 and would not have been built to the grand scale of the Liberty, but would be more cozy and homelike and would be the fall companion to the new airdome.

In the article, Liberty manager A.H. Whitney “said that the location of the Rivoli would not be made public for the present, due to the stage of negotiations for the property on which the house would be located.”

The End of a Glorious Era

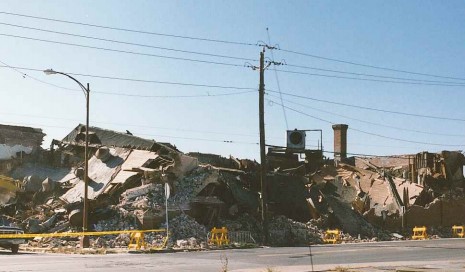

In 1981, Mid-America Theaters, Inc of Sharon Springs, Kansas purchased the 23 theatres owned by Frisina Amusements, including the Liberty and the Little Dixie Airway Drive-In. All 23 were closed within a year. The final movie at the Liberty, “Night Shift”, drew around a dozen patrons on September 30, 1982. The neon and incandescent chasnig lights of the 1940s-era marquee that for generations of Mexicoans spelled an escape from everything from World War II to Vietnam and beyond, went dark.

The building fell into disrepair and was ultimately reduced to a pile of rubble in November of 1995, closing the chapter on the movie palaces, at least by our standards, of Mexico.